Author: Richard Fontaine | Published in Foreign Policy | 8 April 2021

![]() Commentary on the Biden administration’s foreign policy, with its focus on ‘allies and partners’, is currently a hot topic. Every day new articles appear commenting on the challenges for US allies in rallying in support of the new US policies. Mike Scrafton has written on this here, with a focus on Europe and South East Asia, suggesting that the Biden administration has failed to appreciate the implications of the bifurcation of its allies’ economic and strategic interests.

Commentary on the Biden administration’s foreign policy, with its focus on ‘allies and partners’, is currently a hot topic. Every day new articles appear commenting on the challenges for US allies in rallying in support of the new US policies. Mike Scrafton has written on this here, with a focus on Europe and South East Asia, suggesting that the Biden administration has failed to appreciate the implications of the bifurcation of its allies’ economic and strategic interests.

In ‘It’s still hard to be America’s ally‘, Richard Fontaine has written about the challenges for allies – Canada and allies generally – from different angles. While the “administration’s new approach is a breath of fresh air after four years of damage and disparagement,” he writes, “Biden’s welcome celebration of U.S. alliances raises its own set of ambiguities and contradictions. The drive to enshrine a U.S. foreign policy for the American middle class may, in particular, pose new dilemmas for long-term allies.”

Fontaine notes that the tone of the conversation with allies could not be more different under Biden, with a focus on listening to, and consulting and working with allies, and that policy has followed the rhetoric in relation to things like allies’ financial contributions for hosting US troops, and Trump-proposed troop withdrawals.

Nonetheless, he suggests, “dangers lurk under this refreshingly placid surface”. Fontaine identifies three sets of issues that are a cause of tensions:

- Measures to protect US jobs and procurement opportunities that can mean erecting barriers even to close and long-standing allies. “Allies fret that protectionist impulses, unchecked either by the executive branch or Congress, will erode trade opportunities—and with it, the constituency for close ties to the United States.”

- “Entrenched allied policy positions”, for example in relation to economic cooperation with Russia and China, that are a source of US disillusionment.

- The administration’s commitment to elevate democracy and human rights, and approach which “implies collisions with several allies like Thailand, the Philippines, Hungary, and Turkey as well as close partners like Saudi Arabia and the UAE”.

“The final challenge stems from doubts about U.S. steadfastness, often murmured under allied breaths… Should allies join in the “extreme competition” Biden foresees with China or hedge in case his administration eventually seeks broad cooperation? … And with presidential terms at eight years at best, can allies risk siding with U.S. positions if a new leader enters bent on reversing them?”

Fontaine concludes on an optimistic note, however, writing that “messy relationships are nothing new in foreign policy, of course, and no alliance is ever free from complications”. The thorny issues listed above might be called weeds, he suggests (quoting George Schultz), that should be tended to right away. “Identify potential problems early, eliminate what you can, manage what you can’t, and by all means keep them from strangling the greater good in alliance relationships.”

Read the full article (external link to Foreign Policy website)

Richard Fontaine is the chief executive officer of the Center for a New American Security. He worked on the National Security Council staff and at the State Department during the George W. Bush administration.

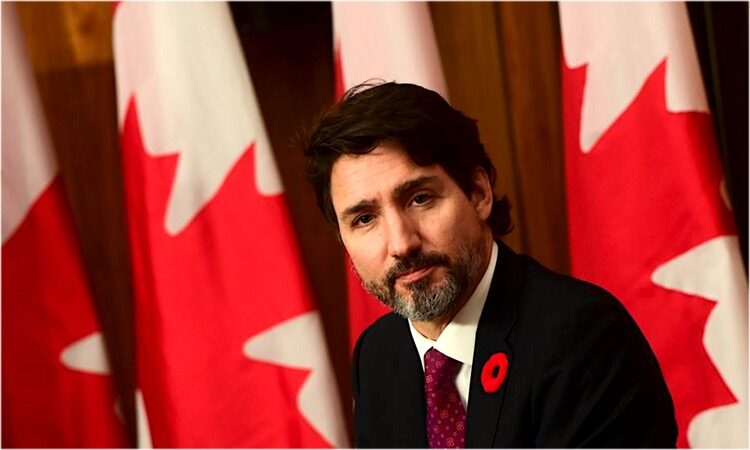

Image: Justin Trudeau, Canadian Prime Minister. Original image, Le Droit