If Mike Pezzullo, Secretary of Home Affairs, were to move to the top Defence job his views on war become of crucial public interest. The government’s reaction to his message to staff on ANZAC Day emphasises this point.

The Westminster system, in form, if not always in substance, maintains a clear distinction between the elected Ministers and the apolitical public service. Individually or collectively, ministers make decisions on government policy after considering objective advice from the public service. However, Pezzullo’s ANZAC Day message represents a major change.

Pezzullo’s deification of the warrior, pushing the creed of war and sacrifice as noble and dutiful, and by inferring those who fail to support the mystique of the warrior lack patriotism, steps beyond the apolitical Westminster model. Suggesting that citizen-electors should accept war as a necessity, he misrepresents the nature of future conflict, positing that the next war will exhibit the characteristics of the last one. These are controversial and polemical political positions not expected from a public servant.

Adherence to the cult of the warrior draws Pezzullo toward the now strategically irrelevant early Cold War thinking of generals who gained their experience in the Second World War. It inspires him to meaningless, pseudo-Churchillian statements about hearing the “drums of war beat” that are inconsistent with rational strategic policy language.

Noticeably, the Prime Minister also subscribes to the warrior cult when he says the ADF members who served in the War on Terror “are the bravest of this generation”. Yes, they were there, they were well-trained and competent, they were well-armed, equipped and supported, and they performed admirably. However, many Australians would have done the same in these circumstances. But the professional serviceman is transformed and elevated into the warrior simply by their choice of a military career. Adulation of the warrior becomes the core of patriotism.

The citizen-soldiers killed during WWII are worthy of remembrance. But why Australians today need to “be prepared to face equivalent challenges with the same resolve and sense of duty that they displayed in years past” is unclear. There is no equivalence, and the moral justification of the Second World War cannot be mounted for many other conflicts; certainly not the First World War or the colonial wars against national independence movements in Asia, the Middle East and Africa.

Pezzullo writes it might again be “the only prudent, if sorrowful, course – to send off, yet again, our warriors to fight the nation’s war”. Prudence encompasses care and thought for the future. Any logic that concludes major war is prudent is not just flawed but reckless. It would not be the basis for formulating sound strategic guidance to government.

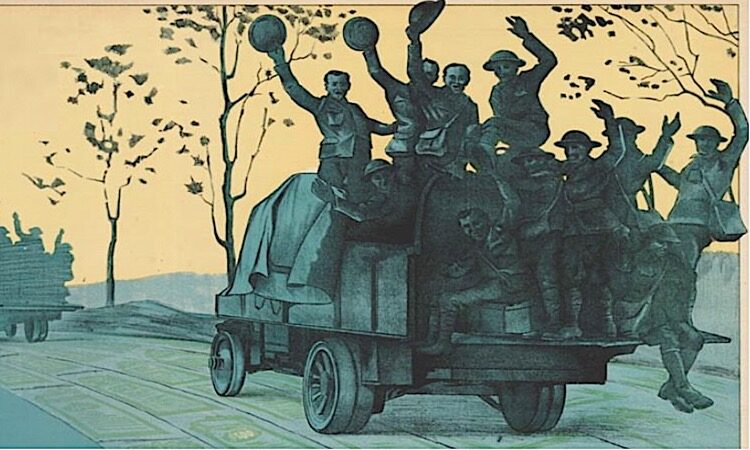

The casualness with which Pezzullo suggests that we send our warriors off with “the very best military strategies and plans”, with “the required machines and war stocks”, and after “all scenarios have been explored and tested, and the strategic assumptions have been challenged and reset” is alarming. Wars have consequences and to embark on them demands clear strategic objectives and an understanding of the prospects for success. To then suggest it will be “left to the rest of us to secure the homeland in their absence, including by way of civil defence” is to argue the next war will be the Battle of Britain rerun in the Pacific.

The warrior cult confuses the efforts of those in uniform and a stoic citizenry with the strategic justification for a conflict. Australians have served well in many wars, including those that they should not have been asked to fight.

The next great power war will be a highly technical, destructive and long-range affair fought with advanced weaponry and platforms, and across land, maritime, air, cyber, and space domains. There won’t be a mass mobilisation, and it will be fought by the force-in-being. We won’t see air-raid wardens and rations cards on the home-front. There won’t be massed forces manoeuvring in theatres far away, and we won’t see D-Day type invasions. Pezzullo’s image of how war might affect Australian citizens is misleadingly anachronistic.

In essence, while not mentioning China, Pezzullo’s words unsurprisingly have been understood as echoing the anti-China warmongering found among some commentators and hints strongly at the current hysteria around Taiwan with the evocation of war-drums.

So how did government deal with a senior public servant stepping into the political limelight in this way. When the Prime Minister was asked, “Do you agree with Michael Pezzullo when he says the drums of war are beating?” he procrastinated and diverted. As he did when asked, “Is it time for people to stop making comments that could be seen as inflammatory or whipping up or sabre rattling?” Morrison was reported elsewhere as saying, “it was not for him to commentate on the Home Affairs secretary’s comments but the government’s objective was ‘to pursue peace’”.

It’s not the Prime Minister’s place to exercise control over public statements made by senior public servants? An astounding proposition!

“Government”, according to the Prime Minister, is “working with our partners in the region, working with ASEAN, working with our Quad partners, working with our comprehensive strategic partners, which includes China” to achieve “peace”. Yet provocative statements from a public servant that are seemingly contrary to stated foreign policy, which was predictably reported across the world, and aroused the ire of China, are not the Prime Minister’s business. This is alien to traditional understandings of the Westminster system.

The whole episode lends itself to speculation. Is Pezzullo road testing a narrative change the government doesn’t feel it can articulate formally yet? Or giving the government a diversion from its vaccine and gender problems? Or is there some sort of hawks versus doves split in the Cabinet and Pezzullo is aligning himself politically with a Peter Dutton putsch? Or perhaps the Home Affairs Secretary is so influential he can’t be resisted?

A move to Defence would make Pezzullo the primary strategic policy adviser to the government. Given his attitude to war and warriors, should Pezzullo ever be Secretary of Defence?

Copyright Mike Scrafton. This article may be reproduced under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence for non-commercial purposes, and providing that work is not altered, only redistributed, and the original author is credited. Please see the Cross-post and re-use policy for more information.

Also published in John Menadue’s Pearls and Irritations.