Australian governments are now certain to be bedevilled by submarines for generations.

The strategic implications of the nuclear-powered submarine decision include an increased likelihood of catastrophic war, abandonment of national sovereignty to the US, and inevitable trade and economic reprisals. First of all, for those who think a submarine capability is important, it is simply bad defence policy.

There are two candidates for this new submarine; the USN Virginia class and the RN Astute class. Both choices bring significant project risks, but there are sound grounds to think that Australia will go with the UK boat, or a version based on the Astute. In either case huge project obstacles face Australia. The USN procurement plans, however, invoke perennial questions about the role of the submarine and the concept of operations. More precisely, are those roles premised on independent Australian defence interests or US war plans? Basing Australian force structuring choices on US war planning is not a surprise (here and here).

The Virginia class is designed for multi-mission dominance in the littoral; originally focussed on Cold War era anti-submarine warfare (ASW), now its primary missions are covert intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), the insertion and recovery of special forces, and missile strikes against land targets. The US navy (USN) has acquired 34 since 1998. However, the US program is in flux. The USN plans to phase out the Virginia class, building the final four between 2032 and 2033.

The Virginia class replacement — designated SNN(X) — is planned to have greater transit speed and stealth in all ocean environments, more diverse weapons and payloads, and a sustained combat presence. It will have a greater ASW capability against numerous sophisticated threats, including against unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs), and be better able to coordinate with off-hull vehicles, sensors, and allies.

The step up in proposed capability to the SSN(X) is reflected in the cost; a Virginia class boat costs US$3.4 billion (AU$4.6 billion) and the estimate for the SNN(X) is US$6.4 billion (AU$8.8 billion) each. Congress is yet to approve the program and the USN has requested US$98.0 million in 2022 for research and development for the SSN(X) program, intending to procure the first vessel in 2034.

The Virginia class and the SNN(X) are optimised for different roles. Because the USN plans to stop building Virginia class before the first Australia vessel is proposed to be launched, and its replacement is not as yet designed or approved, planning on acquiring a US submarine in the middle of a change-over would be fraught in terms of cost, schedule, and capability.

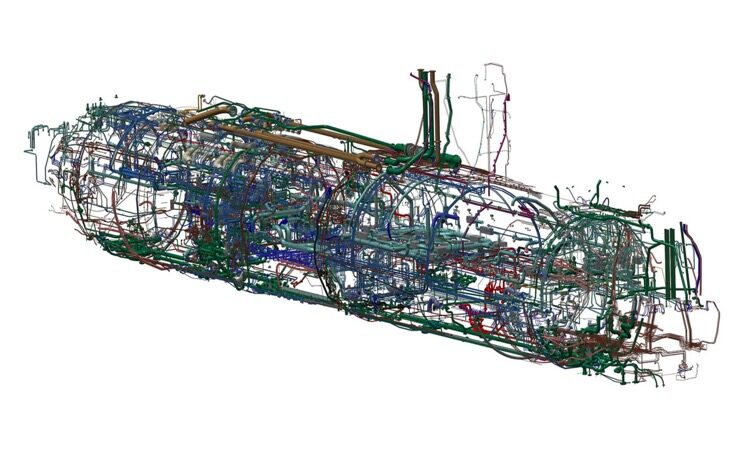

Moreover, there are currently only two shipyards in America capable of building nuclear-powered ships; General Dynamics’ Electric Boat Division (GD/EB) in Connecticut, and Huntington Ingalls Industries in Virginia. The US submarine industrial base includes hundreds of supplier firms, laboratories and research facilities, and many sole-source suppliers. The USN’s requirement for two Virginia-class plus one Columbia-class boats per year from the mid-2020s to the mid-2030s has already created concern about the industrial base’s capacity. It seems unlikely that the first Australian boats could be inserted into that construction program or that an Australian construction could be supported as the USN gears up for the SSN(X).

Similarly, in the UK the Astute class are being built at the Barrow shipyard owned by BAE Systems, the only UK shipyard licensed to build nuclear submarines. The UK uses four main contractors for 97 per cent of its nuclear capability contracts and these in turn use hundreds of sub-contractors, many of which are small and specialist.

The final two of eight Astute class are currently under construction at Barrow and will be launched and commissioned in the mid-2020s. Both the Virginia and Astute programs had significant issues early on, but now the US yards produce boats largely on cost and ahead of schedule, and while costs at the UK yards have settled down, schedules are still dragging. Astute submarines rollout at around £1.64 billion (AU$3.1 billion). An Australian build seems possible in the UK commencing in the late 2020s with the first launch optimistically in the mid-2030s.

The prime minister said, “We intend to build these submarines in Adelaide, Australia, in close cooperation with the United Kingdom and the United States,” although he has apparently conceded the first boats might be built offshore. The practical considerations involved in the South Australian site add additional cost, capability, and schedule risk. Adelaide will need to be accredited to build nuclear powered vessels, but will probably not see any work until the late 2030s. Accessing, or transferring, the myriad of highly sophisticated and specialised services and products that come from small, often sole-source, suppliers currently located in the UK and US will be challenging.

The relevant human expertise is in short supply and the relevant market segments are comprised of either a few major players or a proliferation of smaller niche providers. Contracting in this environment will put pressure on a fefence procurement organisation that has failed in the past in far easier, more familiar transactions. Intellectual property issues and security classifications will prove interesting. The complexities of project management and industry involvement will be enormous.

There can be little confidence that the Australian government can manage this project to a satisfactory end based on past experience. Another shambles is in prospect; an unsupportable and compromised capability, and delivered late and over budget. For the submarine advocates, the situation is worse than before. For Australian citizens, the risks are high and the opportunity cost immense.

Australia will still be without a new submarine capability until the 2040s but the results of the provocation of the nuclear-powered decision will be felt in the near future. Contrary to fantasies of decoupling harboured in various think tanks, Australia’s hubris will see it excluded from the Chinese economy. The ASEAN and the Pacific states will see the paternalism of the English-speaking former colonial powers returning to tell them what they need. This will just enhance Chinese opportunities for influence.

And as the UK retreats from its absurd global Britain delusion and the internally conflicted US retreats across the Pacific, Australia will be alone in the Asia Pacific, possibly without its new toys.

Copyright Mike Scrafton. This article may be reproduced under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence for non-commercial purposes, and providing that work is not altered, only redistributed, and the original author is credited. Please see the Cross-post and re-use policy for more information.

Also published in John Menadue’s Pearls and Irritations.

Image: The intricacy of the pipes and tubes in a submarine. Image from Saab website: https://www.saab.com/newsroom/stories/2020/july/a-submarine-in-space