Authors: Deborah Brautigam and Meg Rithmire | The Atlantic | 6 February 2021

A well-told lie is worth a thousand facts. And the debt-trap narrative is just that: a lie, and a powerful one.

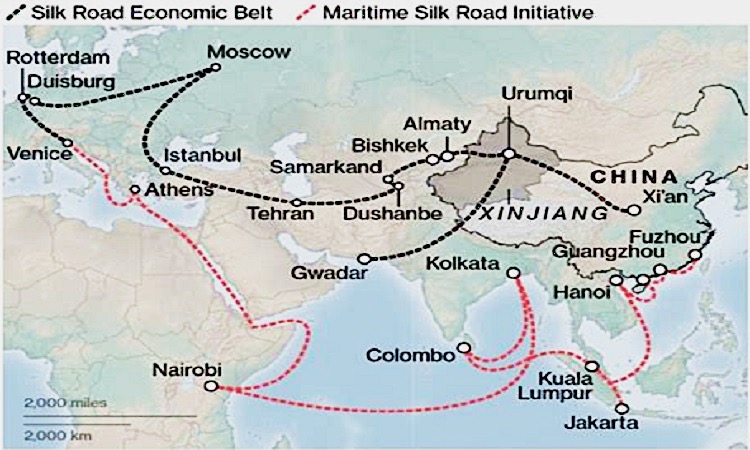

China, we are told, inveigles poorer countries into taking out loan after loan to build expensive infrastructure that they can’t afford and that will yield few benefits, all with the end goal of Beijing eventually taking control of these assets from its struggling borrowers. As states around the world pile on debt to combat the coronavirus pandemic and bolster flagging economies, fears of such possible seizures have only amplified.

Seen this way, China’s internationalization—as laid out in programs such as the Belt and Road Initiative—is not simply a pursuit of geopolitical influence but also, in some tellings, a weapon. Once a country is weighed down by Chinese loans, like a hapless gambler who borrows from the Mafia, it is Beijing’s puppet and in danger of losing a limb.

The prime example of this is the Sri Lankan port of Hambantota. As the story goes, Beijing pushed Sri Lanka into borrowing money from Chinese banks to pay for the project, which had no prospect of commercial success. Onerous terms and feeble revenues eventually pushed Sri Lanka into default, at which point Beijing demanded the port as collateral, forcing the Sri Lankan government to surrender control to a Chinese firm.

The Trump administration pointed to Hambantota to warn of China’s strategic use of debt: In 2018, former Vice President Mike Pence called it “debt-trap diplomacy”—a phrase he used through the last days of the administration—and evidence of China’s military ambitions. Last year, erstwhile Attorney General William Barr raised the case to argue that Beijing is “loading poor countries up with debt, refusing to renegotiate terms, and then taking control of the infrastructure itself.”

As Michael Ondaatje, one of Sri Lanka’s greatest chroniclers, once said, “In Sri Lanka a well-told lie is worth a thousand facts.” And the debt-trap narrative is just that: a lie, and a powerful one.

Our research shows that Chinese banks are willing to restructure the terms of existing loans and have never actually seized an asset from any country, much less the port of Hambantota. A Chinese company’s acquisition of a majority stake in the port was a cautionary tale, but it’s not the one we’ve often heard. With a new administration in Washington, the truth about the widely, perhaps willfully, misunderstood case of Hambantota Port is long overdue.

Read the full article (external link to The Atlantic)

Deborah Brautigam is Bernard L. Schwartz Professor of International Political Economy at the School of Advanced International Studies at Johns Hopkins University. Meg Rithmire is F. Warren McFarlan Associate Professor at Harvard Business School.

Image: By Ben Schmulevitch for The Atlantic

![]() This article is a useful addition to a growing body of work emerging from researchers and development practitioners that counter certain narratives about Chinese infrastructure and development loans and contracts.

This article is a useful addition to a growing body of work emerging from researchers and development practitioners that counter certain narratives about Chinese infrastructure and development loans and contracts.

- The authors’ research confirms others’ findings that Chinese loans are generally sought out by the borrower and that the terms of the loans are usually shaped by the borrower, not by the Chinese lender.

- The article illustrates once again that American, European and other countries’ banks and firms are also very much part of the international infrastructure development landscape, and often need to be a part of conversations about failing projects and unsustainable debt levels.

- The authors’ analysis dispels the notion of “debt-trap diplomacy” that “casts China as a conniving creditor and countries such as Sri Lanka as its credulous victim”, but highlights how widespread the idea has become in political rhetoric – an idea that not only gives a potentially inaccurate picture of China’s motivations and conduct, but also, and equally unhelpfully, portrays the credit recipient countries as having little agency, autonomy or capacity to know what is in their best interests.

Assigning a malign purpose to every Chinese action is not just poor logic (poor analysis). It leads to making poor judgements that in turn will drive ineffective or even harmful policy choices. The Hambantota example proves the point. Operating from the premise that everything the Chinese do is directly related to the geostrategic struggle with the US, the conclusion that follows is always that the particular activity under consideration is malign. The conclusion is assumed before the facts and circumstances are examined.

The geostrategic frame doesn’t fit neatly over the Hambantota issue. China does not have the control over the port that has been claimed. The port is highly unsuitable as a naval base for the projection of Chinese maritime power into the Indian Ocean. The investment by the Chinese hasn’t given them sway over Sri Lanka’s foreign policy. The Sri Lankan government has exercised its legitimate autonomy and agency in relation to the project. The project is not evidence of a malign act tied to geostrategic plans.

There are many activities that the Chinese engage in that are part of their competition with the US, but most of China’s international commercial, financial, and trade ventures are, on examination, much more closely related to Chinese economic interests. As is the case with all great powers it is difficult, if not impossible, to separate economic and commercial activities from the political and strategic interests of the states. They are intertwined; trade follows power and power grows with trade. But judgements need to be made about the characteristics and potential of individual activities within their settings, and of general trends in activities, before forming judgements about relative importance.