President Trump’s approach to foreign and strategic policy accorded little weight to the views and interests of America’s allies, and alliances were primarily viewed as transactional arrangements. Richard Armitage and Joseph Nye have collaborated on developing a set of so-called “bipartisan” recommendations for at least one of these alliances of the post Trump era. Their proposals for the US-Japan alliance, however, betray the Manichean world view that possesses Washington and a lingering conviction of exceptionalism, while indirectly acknowledging that global leadership is now beyond America’s reach.

The change in political leadership in both Japan and the US creates very different situations for both nations. Prime Minister Suga must be relieved that his assumption of the office coincides with the end of the disruptive and unpredictable Trump Administration and the ascension of a more traditional president in Joe Biden. In Washington there will be some unease about the handover from Shinzo Abe and what that might mean for Japan’s foreign policies. Perhaps the uncertainty and the space opened up by these transitions were the motivation for Armitage and Nye.

It’s difficult to shake-off the impression that Armitage and Nye are to some degree resentful that during the years of the Trump Administration Japan has not only acted in accord with its own interests, it has assumed a more prominent global role. When they say “inconsistent leadership in the United States has empowered Japan to lead on strategic issues in Asia and the rest of the world”, they suggest that absent the Trump interregnum Japan would have dutifully followed in America’s footsteps. When they write “Japan has become not just an essential and more equal ally but also an idea innovator” they apparently don’t hear the implied condescension. They seem surprised.

On the other hand, there is a clear recognition by Armitage and Nye that the US now has to piggyback off the prestige and authority Japan that has acquired internationally. This theme dominates their thinking. They argue that “a more equal U.S.-Japan alliance is critical to addressing both regional and global challenges”. They acknowledge “Japan is the ally most aligned with U.S. interests and values across the board” and concede that during the Trump years Japan has “already taken the lead, promoting shared values, high standards, and liberal norms”. It is, they say, “the United States [that] would benefit from closer alignment with Tokyo’s approach in a number of areas”. It suits the US now, because ”There was a time when Japanese initiative might have prompted concerns in Washington, but it is clear today that Japan’s strategy aligns well with U.S. objectives”.

However, the US, in the view of Armitage and Nye, and despite their protestations, still must take the lead. They say “there is strong reason to believe that the United States can move forward with a positive agenda for the U.S.-Japan alliance”. They insist that “The United States must reset the conversation and conclude a Host Nation Support Agreement “. Downplaying the deep historical roots that shape relations between South Korea and Japan, it is the United States that “needs its two allies in Northeast Asia to work together constructively and pragmatically” and should tell them “to focus on the future, not the past”. To accommodate the US’s interest in joining the Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP) “the new administration may reasonably expect changes to the CPTPP.” Joining would enable the US “to align with Japan as leaders in shaping economic rules”, while not joining poses “a larger risk to U.S. prosperity and security”.

Two judgements that emerge clearly from the joint Armitage and Nye effort are that Japan has creatively asserted itself as a leading power and that the US can no longer hope to take a hegemonic stance. Their conclusion is that for the US to pursue its interests effectively it needs to partner with other nations. The unipolar moment has passed. They believe “The U.S.-Japan alliance is positioned to lead in the evolving multipolar world”. This is a blatantly myopic perspective that ignores, not just the fact that China will not be a passive bystander, but, that many other players like the European Union, Turkey, India, and in Africa and South America, are increasingly valuing their strategic autonomy. It seems that the world is seeking partners not leaders.

Richard Armitage and Joseph Nye are long time pillars of the Washington national security policy elite. It is deeply refreshing to see them acknowledge that there is no going back to US hegemony. The world has changed. The power and the prestige of the US has weakened and China is a reality. The space has opened up for states like Japan to pursue their own interests in cooperative and mutually beneficial ways. The US will have to partner with not just Japan but all other states, and compromise some of its interests in the common good, if it wishes to have influence. In a limited, and still too self-interested way, Armitage and Nye have given the discussion a good, if unintended, boost.

Copyright Mike Scrafton. This article may be reproduced under a Creative Commons CC-BY-NC-ND 4.0 licence for non-commercial purposes, and providing that work is not altered, only redistributed, and the original author is credited. Please see the Cross-post and re-use policy for more information.

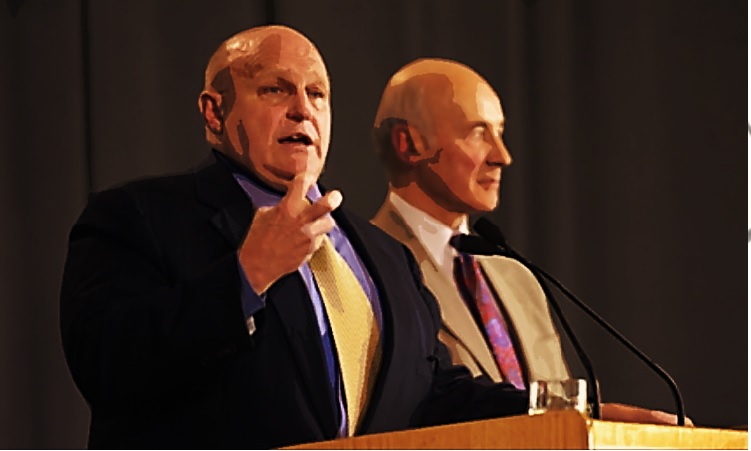

Image: Richard L. Armitage and Joseph S. Nye Jr. Original photo Harvard.

Related content

The US-Japan alliance in 2020: an equal alliance with a global agenda (Armitage-Nye)